Better Software Design with Application Layer Use Cases | Enterprise Node.js + TypeScript

The term Use Case is used to describe one of the potential ways that our software can be used.

Another word that's sometimes used is feature, though the concept is nearly identical.

The whole purpose of building software is to address one or more Use Cases.

In large projects, it can sometimes be hard to determine what the capabilities of the system are.

That's incredibly true on CRUD apps designed API-first.

What if there was a particular construct that actually appeared in our code that would describe all of the different capabilities of our app?

Something that would help towards encapsulating, organizing, and keeping track of all of the things that our application is capable of.

Well, it does exist, and it's properly called: you guessed it, a Use Case.

In the Clean Architecture, Use Cases are an application layer concern that encapsulate the business logic involved in executing the features within our app(s).

In this article, we'll cover the following topics towards structuring Node.js/TypeScript applications using Use Cases in the application layer:

- How to discover Use Cases

- The role of the application layer

- How to identify which subdomain Use Cases belong in

- How Use Cases make large projects more readable (screaming architecture)

- How to implement Use Cases with TypeScript

To see the code used in this article, check out:

https://github.com/stemmlerjs/white-label

Discovering Use Cases

There are several different ways to plan out building an application. For a long time, I simply planned out how I would actually build something by designing the API first.

Later on, I ended up moving more towards wire-framing and starting from the interface first, because the front-end would often dictate what's really needed and what's YAGNI.

It wasn't until the projects I started working on got so complex that I realized I needed to take a more traditional approach to software planning: Use Case design.

Traditional approach

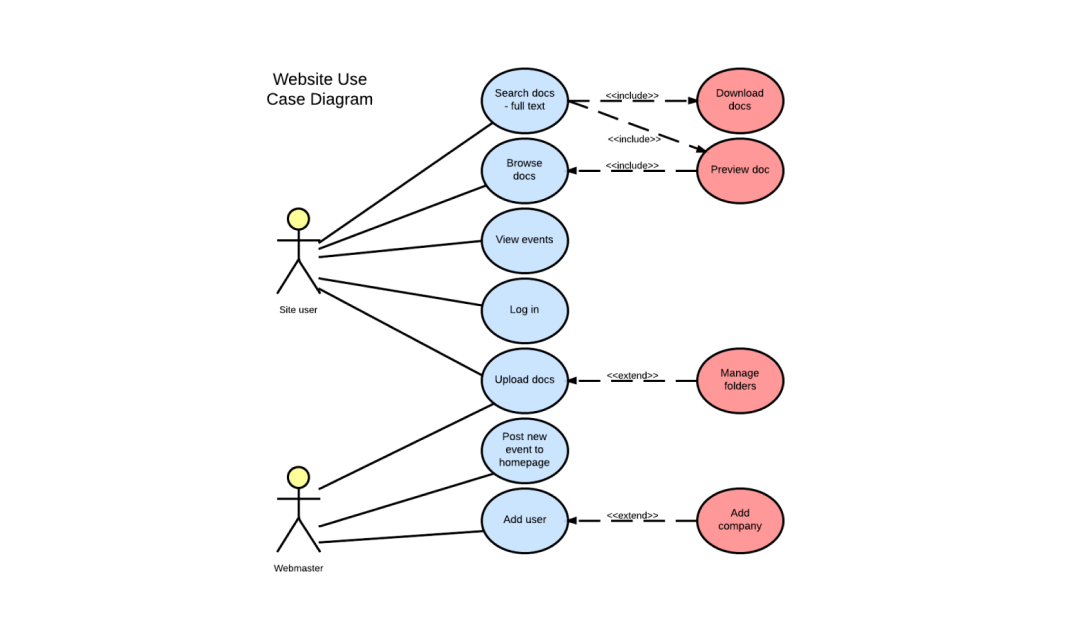

There's a traditional approach to identifying and drawing Use Cases using a Use Case Diagram.

In Use Case Diagrams, the stick-man represents an actor of our system (someone who uses it), and the circles represent all of the actual use cases that we'd like to enable them to execute with our software.

I think it's a good to know how to create these, but rarely do I ever start designing a system with the sole purpose of generating one of these documents.

Instead, I try to identify the essential components through conversation and draw things out using a kind of free-form approach.

Use Case Basics

The most important things to understand about identifying use cases are:

-

- Who the

actorsof the system are (who's executing the use cases)

- Who the

-

- That use cases are either commands or queries

-

- That use cases belong to a particular subdomain which may be deployed on separate bounded contexts

1. Actors

It's easy to just call every actor a User. We could do that, but it doesn't say much about the domain itself.

There's a time and place to call a user a User, like in an Identity & Access Management subdomain like Amazon IAM or Auth0, but we should try to be as expressive as we can about identifying the actual actors in our systems by thinking about their role in the domain.

Here are some alternatives to User depending on the domain:

- A billing system:

Customer,Subscriber,Accountant,Treasurer,Employee - A blogging system:

Editor,Reviewer,Guest,Author - A recruitment platform:

JobSeeker,Employer,Interviewer,Recruiter - Our vinyl-trading application:

Trader,Admin - An email marketing company:

Contact,Recipient,Sender,ListOwner

Get the point? Role matters.

2. Use Cases are Commands and Queries

A Use Case will be either a command or a query.

There's an entire object-oriented design principle dedicated to this phenomenon called CQS (Command-Query Segregation). When you follow it, it helps to make application side-effects easier to reason about and aids in reducing bugs and improving readability.

For example, in our Vinyl-Trading app, "White Label", an example of a particular command is to add vinyl to our wishlist. That might appear in our code as a class called AddVinylToWishlist.

An example of a query would be to get our wishlist, which might appear as GetWishlist.

In Command-Query Segregation, COMMANDS perform changes to the system but return no value, and QUERIES pull data out of the system, but produce no side effects.

3. Use cases belong to a particular subdomain

Generally speaking, most applications are built up of several subdomains.

If you don't remember what a subdomain from domain-driven design is, it's a logical separation of the entire problem domain.

A subdomain is a logical separation of the entire problem domain.

What's the problem domain?

For example, White Label, the Vinyl-Trading app that I'm building, is about trading vinyl.

But the problem domain isn't only about enabling traders to trade vinyl. There's much more that needs to be accounted for.

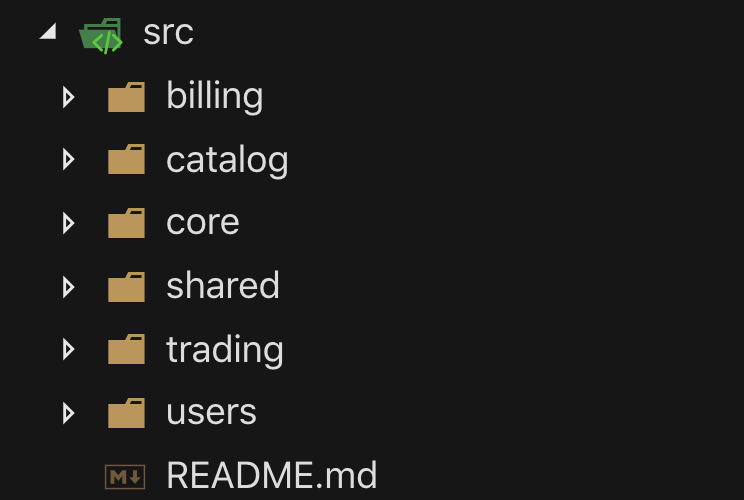

In addition to the trading aspect (Trading), the enterprise also has to account for several other subdomains: identity and access management (Users), cataloging items (Catalog), billing (Billing), notifications and more.

This is the essence of Conway's Law which states:

"Organizations that design systems, are constrained to produce designs that are copies of the communication structures of these organizations."

Conway's law actually helps answer a lot of questions like:

- how do we decide on our subdomains?

- how do we decide which subdomain a use case should belong to?

- how do we make it easier to change use cases in the future?

For more on Conway's Law and how it can help make these decisions, check out this article.

In any domain-driven project, we're usually able to decompose the entire problem domain into separate subdomains; some of which are essential that we develop ourselves (like the Trading and probably Catalog subdomain), and some of which we might be able to just use a vendor (like Auth0 for Users & Identity or Stripe for Billing).

Large monolith applications with minimal coupling between subdomains are said to be logically separate.

If our fictional enterprise application needed to scale out, that logical separation would be essential in order for us to physically separate our problem domain into several independently deployable units.

In other words: microservices.

In DDD-lingo: separate bounded-contexts.

We discover use cases through conversation

A huge misconception about software development is that developers just code away in the corner and never have to talk to people.

That's so not true. So much of software development (especially in DDD) is consistently attempting to identify the correct language to effectively create a lasting software implementation of the model from real life.

Here's an example of the conversation to discover some of the Use Cases in White Label.

"So, I have this idea for an app. It's an app where you can trade vinyl with other people."

"OK, cool. So like, Discogs?"

"Yeah, pretty much. But it's only for vinyl. True hipsters."

"Awesome, I like it. What if I don't want to trade my vinyl? Can I just buy something?"

"Yeah, let's say: you can either trade your own vinyl for someone elses, or you can trade them money for it instead."

"Oh, what about this? Users can make complex offers, like hey, I'll give you these 2 Devo albums, a Sex Pistols album and 60 bucks for that limited edition Birthday Party vinyl".

"Ah, so there's offers and trades. And an offer can include several records and/or money in exchange for one or more records. And the person who receives the offer can either accept it, or decline the offer."

"Yeah, that sounds pretty accurate. And if they want to decline it, they can decline 'with comments' or something, saying why they decline it, and give them another reason to make another offer."

"Yeah ok cool."

"So what are the use cases we've discovered so far?"

"

MakeOffer(offer: Offer)DeclineOffer(offerId: OfferId, comments?: string)AcceptOffer(offerId: OfferId)

"

"Probably also the ability to get all the offers, and get an offer by id. We have to think about the UI as well. It's going to need some use cases."

"Ah, yes. So also GetAllOffers(userId: User), GetOfferById(offerId: OfferId)".

"Hmm, where did User come from?"

"That's what we've been talking about this whole time, no? Things Users can do."

"Yeah, but not really. Let's think about the Ubiquitous Language here. With respect to this Trading subdomain and their role, it would make more sense to call them Traders, or RecordCollectors.

"Ahh, I see, the term User probably belongs more in a Users & Identity subdomain, not a... Trading subdomain, which is what we've been discussing so far, right?"

"Yeah, that's right."

"OK, let's go with Traders."

"Awesome. So far, in the Trading subdomain, the Use Cases we have are:

MakeOffer(offer: Offer)DeclineOffer(offerId: OfferId, comments?: string)AcceptOffer(offerId: OfferId)GetAllOffers(traderId: TraderId)andGetOfferById(offerId: offerId)

I can't think of anything else yet."

"Me neither, let's go with that for now."

"And it looks like we've identified some of the Entities as well. Offer and Trader, right?"

"Yeah, Offer is probably going to be an Aggregate Root for all of the OfferItems as well (a collection of money + vinyl). We can figure that out later. Sounds good so far.

"Oh, and since we brought up the Users & Identity subdomain, should we address that as well?"

"Eh, yeah- we could. It's probably going to be the same as every other app."

"What do you mean?"

"Well, the use cases are pretty common. There's normally like something like:

login(userEmail: UserEmail, password: UserPassword)logout(authToken: JWTToken)verifyEmail(emailVerificationToken: EmailVerificationToken)changePassword(passwordResetToken: Token, password: UserPassword)

You know what I mean? You've probably done this plenty of times."

"Ah, isn't that something we could probably outsource?"

"Yeah, we could probably try Auth0 for that."

"What do they call that in DDD-lingo, again? The type of subdomain..."

"A generic subdomain."

"Meaning?"

"Meaning while it might be a critical part of the business, yeah, it's not the core of the business. The core is probably going to be the Trading subdomain".

"Right. That'll be the core subdomain because that's essentially the unique thing about our app that can't just be outsourced or bought off the shelf."

The role of the Application Layer

If you've been following the series on Enterprise Node.js + TypeScript, you'll recall that the Domain Layer holds all of the entities, value objects, has 0 dependencies to outer layers, and is the first place that we aim to place business logic, especially if it pertains to one particular entity.

For example, in White Label, if I were trying to figure out where to place invariant logic that would ensure that a Vinyl can only have up to at max 3 different Genres, that logic would belong in the Vinyl class (which is an aggregate root).

class Vinyl extends AggregateRoot<VinylProps> {

...

addGenre (genre: Genre): Result<any> {

if (this.props.genres.length >= MAX_NUMBER_OF_GENRES_PER_VINYL) {

return Result.fail<any>('Max number of genres reached')

}

if (!this.genreAlreadyExists(genre)) {

this.props.genres.push(genre)

}

return Result.ok<any>();

}

}Vinyl is one of many domain models from the Domain Layer from the Catalog subdomain.

OK, so we generally understand what the Domain layer is for. And we remember that the infrastructure layer contains external services and things that we don't want to muddy our inner layers with (controllers, databases, caches, etc).

So then, what's the role of the application layer?

The application layer contains the Use Cases for a particular subdomain in our application.

The use cases describe the features of the application, which may be independently deployed or deployed as a monolith.

That means that when we put the use cases directly into a subdomain, we can understand the capabilities of that subdomain right away.

In DDD-lingo, Use Cases are the application services. They're responsible for retrieving the domain entities in addition to the information that they need in order to execute some domain logic.

For example, in the AcceptOffer(offerId: OfferId) use case, all I have is the OfferId. That's not enough for me to do the accept action. I'm going to need the entire offer entity in order to save offer.accept() and dispatch a OfferAcceptedEvent domain event. To get the offer, I'll need to use a repository to retrieve & save it. That's how they're responsible for retrieving and spinning up an execution environment with domain entities.

Let's look at how we might structure a project around use cases.

Structuring projects around use cases

Uncle Bob identified a pattern called "Screaming Architecture". It means that by just looking at the project structure itself, it should be figuratively screaming at us: the type of project we're working on, in addition to the capabilities of the system.

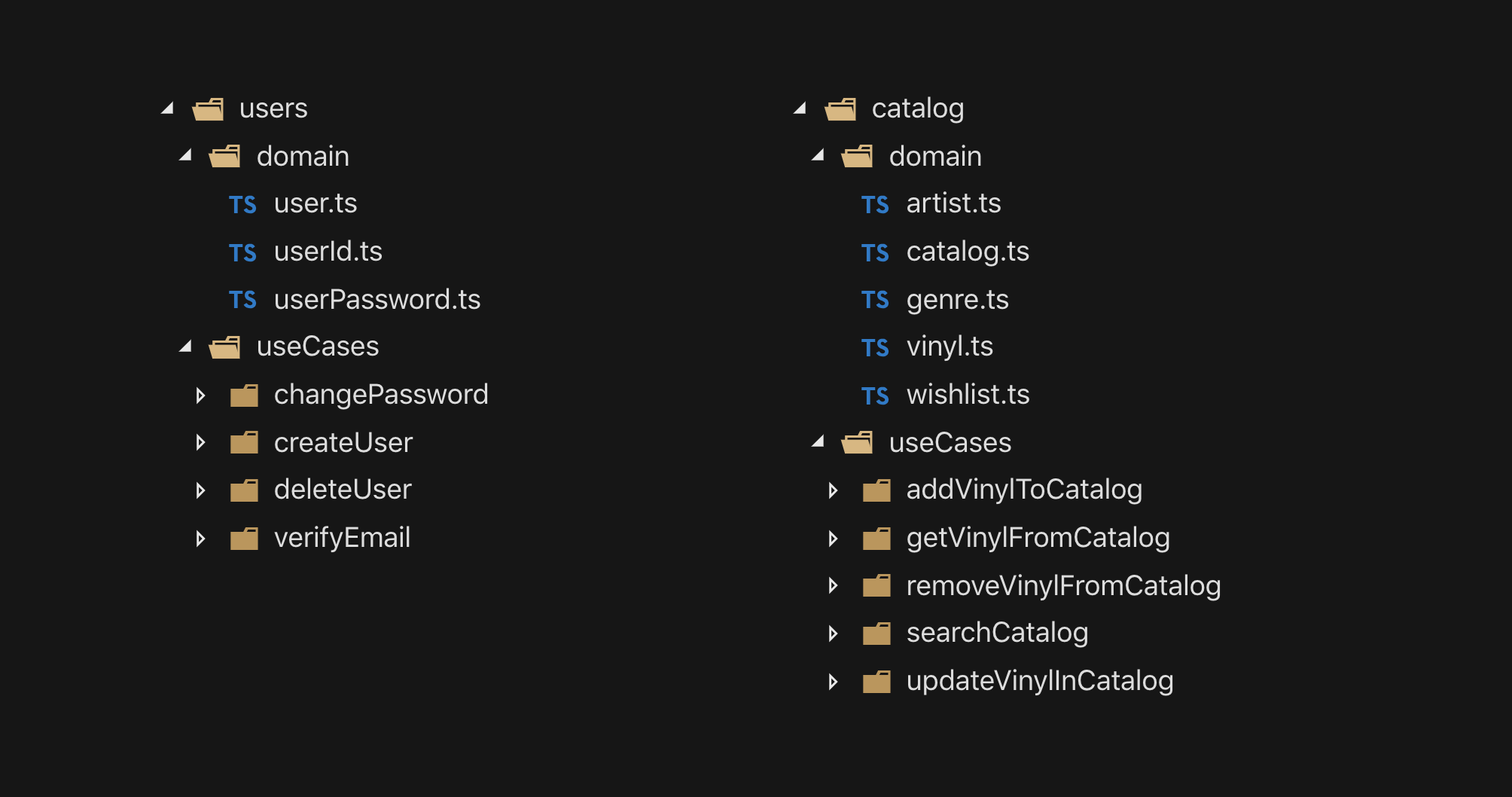

Here's a little bit of what it looks like in White Label when we split it into Subdomain => Use Cases + entities.

At a glance, this tells us a ton about what the users subdomain is and what it does, in addition to what the catalog subdomain is and what it does.

A Use Case interface

Use Cases are simple in principle. They have an optional request and response.

export interface UseCase<IRequest, IResponse> {

execute (request?: IRequest) : Promise<IResponse> | IResponse;

}Employing the design principle of "always programming to an interface and not an implementation", we can create an interface to represent a Use Case like this.

Simple enough, right?

Implementing a Use Case

Let's take a look at how we might implement this. Let's do the AddVinylToCatalogUseCase from the Catalog subdomain.

First, we'll create the class and implement the interface, using any for the Generic DTOs (data transmission objects).

export class AddVinylToCatalogUseCase implements UseCase<any, any> {

public async execute (request: any): Promise<any> {

return null;

}

}Alright, so in order to update a Vinyl, we need to provide everything necessary in order to create it, in addition to the Trader's id that we're adding it to.

Let's put all of that in the request DTO.

interface AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO {

vinylName: string;

artistNameOrId: string;

traderId: string;

genresArray?: string | string[];

}

export class AddVinylToCatalogUseCase

implements UseCase<AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO, any> {

async execute (request: AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO) : Promise<any> {

return null;

}

}We're ready to actually implement the use case algorithm now.

Since our Vinyl aggregate root class needs an actual instance of an Artist, we'll have to determine whether to retrieve the artist by id or by artistName.

If the request fails, we'll use our result class to safely return an error, otherwise we'll use a VinylRepo to save the Vinyl to persistence.

So we'll need to use Dependency Injection to inject a VinylRepo and an ArtistRepo.

We can include that as a dependency in the constructor for this class.

interface AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO {

vinylName: string;

artistNameOrId: string;

traderId: string;

genresArray?: string | string[];

}

export class AddVinylToCatalogUseCase

implements UseCase<AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO, Result<Vinyl>> {

private vinylRepo: IVinylRepo;

private artistRepo: IArtistRepo;

constructor (vinylRepo: IVinylRepo, artistRepo: IArtistRepo) {

this.vinylRepo = vinylRepo;

this.artistRepo = artistRepo;

}

public async execute (request: AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO): Promise<Result<Vinyl>> {

return null;

}

}Alright, now let's hook up the logic.

export interface AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO {

vinylName: string;

artistNameOrId: string;

traderId: string;

genresArray?: string | string[];

}

export class AddVinylToCatalogUseCase

implements UseCase<AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO, Result<Vinyl>> {

private vinylRepo: IVinylRepo;

private artistRepo: IArtistRepo;

constructor (vinylRepo: IVinylRepo, artistRepo: IArtistRepo) {

this.vinylRepo = vinylRepo;

this.artistRepo = artistRepo;

}

public async execute (request: AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO): Promise<Result<Vinyl>> {

const { vinylName, artistNameOrId, traderId, genresArray } = request;

let artist: Artist;

const isArtistId = TextUtil.isUUID(artistNameOrId);

if (isArtistId) {

artist = await this.artistRepo.findById(artistNameOrId);

} else {

artist = await this.artistRepo.findByArtistName(artistNameOrId);

}

if (!!artist) {

artist = Artist.create({

name: ArtistName.create(artistNameOrId).getValue(), genres: []

}).getValue();

}

const vinylOrError = Vinyl.create({

title: vinylName,

artist: artist,

traderId: TraderId.create(new UniqueEntityID(traderId)),

genres: []

});

if (vinylOrError.isFailure) {

return Result.fail<Vinyl>(vinylOrError.error)

}

const vinyl = vinylOrError.getValue()

await this.vinylRepo.save(vinyl);

return Result.ok<Vinyl>(vinyl)

}

}That's it! Now how do we hook this up to our application?

Use cases are infrastructure-layer concern agnostic

Use Cases are agnostic to how we hook them up.

As long as we can provide the inputs, they can execute commands and queries on our system.

That means that they can be hooked up by Express.js controllers or any other external services from the infrastructure layer.

import { BaseController } from "../../../../../infra/http/BaseController";

import { AddVinylToCatalogUseCase } from "./CreateJobUseCase";

import { DecodedExpressRequest } from "../../../../../domain/types";

import { AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO } from "./AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO";

export class AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseController extends BaseController {

private useCase: AddVinylToCatalogUseCase;

public constructor (useCase: AddVinylToCatalogUseCase) {

super();

this.useCase = useCase;

}

public async executeImpl (): Promise<any> {

const req = this.req as DecodedExpressRequest;

const { traderId } = req.decoded;

const requestDetails = req.body as AddVinylToCatalogUseCaseRequestDTO;

const resultOrError = await this.useCase.execute({

...requestDetails,

traderId

});

if (resultOrError.isSuccess) {

return this.ok(this.res, resultOrError.getValue());

} else {

return this.fail(resultOrError.error);

}

}

}Use cases can also be executed by other Use Cases from within the application layer as well (but not from the Domain-layer as per Uncle Bob's Dependency Rule). And that's really cool.

Elegant usage of Use Case with Domain Events

There's actually a really elegant way to chain Use Cases together.

You'd want to chain Use Cases together when one event might trigger another Use Case to be executed in certain scenarios. In Domain-Driven Design, we'd identify this behaviour through an Event storming exercise and use the Observer pattern to emit Domain Events.

Notifying traders when an item from their wishlist is added

In White Label, traders can add either artists or specific vinyl to their wishlist. Whenever someone adds a new vinyl to their collection, traders that are interested in that particular vinyl or artist will be notified that it was posted. That way, they can make an offer to the owner for the vinyl that they're interested in.

The following diagram is a simplification of the communication between layers and use cases.

At scale, if we wanted to deploy our subdomains as microservices instead of running it as a monolith in a single process, we could utilize a message broker like RabbitMQ or Amazon MQ.

We'll follow up with the nitty-gritty on hooking up Domain Events to execute chained Use Cases in a de-coupled way using the observer pattern in a future article.

Codebase

All the code in this article is from White Label, a Vinyl-Trading enterprise app built with Node.js + TypeScript using Domain-Driven Design. You can check it out on GitHub:

Stay in touch!

Join 20000+ value-creating Software Essentialists getting actionable advice on how to master what matters each week. 🖖

View more in Enterprise Node + TypeScript