Knowing When CRUD & MVC Isn't Enough | Enterprise Node.js + TypeScript

If you're a developer, you've most definitely heard about MVC.

It's the most popular and well-understood architecture for creating applications that involve user interfaces.

For a lot of developers, myself included, MVC is the first type of architecture we learn about, and it's our introduction to full-stack web development.

As a founder ex co-founder @ Univjobs, an early-stage startup a very, very dead startup, I've realized that MVC is amazing because it will enable you get things done fast as hell.

And getting things done fast in order to validate them quickly is one of the most important things about engineering in a startup.

But I've also discovered that MVC (the way it's been popularized, at least) is not going to cut it for enterprise applications.

The biggest challenge in complex apps is that the M in MVC doesn't describe how to organize your business logic.

In this article, I'll cover:

- How to reason about using ORMs directly in CRUD apps

- How to identify when CRUD apps have become too complex

- How domain modeling can bring structure to the 'M' part of MVC

MVC Basics

The view in MVC is the visual representation of our app. It might show us charts, diagrams, forms, etc. This is our window into the application as end users.

The controller is an artifact should:

- wait for HTTP requests

- delegate business logic to models and services and saves the result of that transaction to persistence (sometimes we don't do this)

- return a meaningful response

Lastly, the model is meant to handle all of the rules, logic and data.

Models in popular ORMs

The model has the most unclear role out of all of the parts of MVC.

I think a large part of the confusion is that when people think of a Model, they think of an ORM (object-relational mapping) tool.

It’s a common practice in Node.js backend applications to use an ORM in order to interact with the database.

Models in MongoDB with Mongoose

let mongoose = require('mongoose')

let validator = require('validator')

let emailSchema = new mongoose.Schema({

email: {

type: String,

required: true,

unique: true,

lowercase: true,

validate: (value) => {

return validator.isEmail(value)

}

}

})

module.exports = mongoose.model('Email', emailSchema)Models in Sequelize

module.exports = (sequelize, type) => {

return sequelize.define('user', {

id: {

type: type.INTEGER,

primaryKey: true,

autoIncrement: true

},

name: type.STRING

})

}Models in TypeORM

import {Entity, PrimaryGeneratedColumn, Column} from "typeorm";

@Entity()

export class User {

@PrimaryGeneratedColumn()

id: number;

@Column()

firstName: string;

@Column()

lastName: string;

@Column()

age: number;

}In each of these examples, the Model is a single file which defines the table or object schema.

The next question that people start to ask is:

Where does my business logic go?

It's supposed to be a part of the model, right? Since we only have 3 components to MVC, and we're sure it's not in the controller and we're absolutely sure it's not in view, it's the model.

But how? Our ORM models are so slim. They're just definition files.

And even moreso, each of these ORM models are infrastructure concerns.

Putting business logic directly in the ORM objects (which are neat implementations of the Active Record Pattern) is a violation of the Separation of Concerns principle in a Clean Architecture.

So then where does the business logic go?

Because we don't want to put logic directly in our ORM model, we take shortcuts.

Sometimes, we end up putting everything in the controller.

Sometimes, we end up creating services and putting it in that.

And quite honestly, doing that isn't always a bad thing. It all depends on the context.

In my opinion, whether or not that's a bad thing can be determined by the answer to this question.

Are you building a CRUD app or are you building a complex app?

CRUD apps

You might recall that CRUD stands for Create, Read, Update and Delete.

In CRUD applications, there's not a whole lot of business logic.

With CRUD apps, we'll often design them REST-first because they fit so perfectly into RESTful APIs.

A RESTful API call can be reasoned to be:

the combination of a route (ie: which model(s) to interact with), and a method (how to interact with the specified model(s))

GET /users // GET the user model (collection)

DELETE /user/:userId // DELETE a particular user

POST /user/new // CREATE a new userIn REST-first apps, there's very little actual business logic that needs to take place, and using our ORMs directly from the controller or service will allow us perform operations on our models quickly.

The role of ORMs in simple CRUD apps

Take this example.

class UserController extends BaseController {

async createUser (req, res) => {

try {

const { User } = models;

const { username, email, password } = req.body;

const user = await User.create({ username, email, password });

return res.status(201);

} catch (err) {

return res.status(500);

}

}

}Look at how simple that is to understand.

And it probably took us no time to do.

Although, we are now relying on the database to perform validation logic (yep, that's a form of business logic). However, we might be willing to sacrifice that in order to get something up and running quickly (for the better approach, see how Value Objects in DDD addresses this).

But just notice that as soon as we were to add any sort of additional validation logic to this controller, we would be writing code somewhere that it probably doesn't belong.

This leads us to doing quick fixes such as creating several helper files and folders and moving validation logic to services.

That's one way to build an Anemic Domain Model and scatter plenty of domain logic throughout an app without knowing it.

Ultimately, it's not a bad idea to build anemic domain models and refer to our ORMs directly from the services and controllers when we're working on simple CRUD apps.

You can go hella fast.

This is what early-stage startup code is made of.

But things start to get a little bit out of hand when apps grow in complexity.

Story time: What when happens CRUD apps turn complex

Univjobs is a niche job board for students and recent-grads.

When new jobs get posted by employers, we have to verify them before they go live in the app so that students don't get taken advantage of by employers who want to pay them less than minimum wage.

This means we needed a way to approve a job posting.

The moment I realized things were about to get a lot less CRUD-y was when I defined a method in a service class called postJobCreatedHooks(jobId: string).

function postJobCreatedHooks (jobId: string) {

// Charge the customer.

// Add the job to our queue of new jobs for the week.

// Trigger a gatsby build to rebuild our Gatsbyjs site.

// Post the job to social.

// Do a bunch of other stuff.

// Send an email to the customer letting them know their job is active.

}WHOA THERE.

We did all of that in a single method JobService method. Of course it was broken up and other services were injected, but that's a lot for a JobService to have to know about. That also seems like a blatant violation of the Single Responsibility Principle.

I wanted to do something after the Job model changed in a particular way (from verified = false to true).

The thing is, a lot of these ORMs actually have mechanisms built in to execute code after things get saved to the database.

For example, the Sequelize docs has hooks for each of these lifecycle events.

(1)

beforeBulkCreate(instances, options)

beforeBulkDestroy(options)

beforeBulkUpdate(options)

(2)

beforeValidate(instance, options)

(-)

validate

(3)

afterValidate(instance, options)

- or -

validationFailed(instance, options, error)

(4)

beforeCreate(instance, options)

beforeDestroy(instance, options)

beforeUpdate(instance, options)

beforeSave(instance, options)

beforeUpsert(values, options)

(-)

create

destroy

update

(5)

afterCreate(instance, options)

afterDestroy(instance, options)

afterUpdate(instance, options)

afterSave(instance, options)

afterUpsert(created, options)

(6)

afterBulkCreate(instances, options)

afterBulkDestroy(options)

afterBulkUpdate(options)In order to hook one of these up, you'd hook it up to your ORM model definition file.

Like this for example:

class Job extends Model {}

Job.init({

title: DataTypes.STRING,

status: {

type: DataTypes.ENUM,

values: ['initial', 'verified', 'rejected']

}

}, {

hooks: {

afterSave: (job, options) => {

// do all our domain logic here?

}

},

sequelize

});But there we go again... We're back to violating the Separation of Concerns at the architectural level.

We don't want to put Domain layer business logic in an infrastructure concern.

And even if we were OK with doing that, surely, it wouldn't be a good idea to pollute our Model with service calls in order to do all this stuff.

hooks: {

afterSave: (job, options) => {

if (job.status === 'verified' && options.status !== 'verified') {

// Charge the customer.

// Add the job to our queue of new jobs for the week.

// Trigger a gatsby build to rebuild our Gatsbyjs site.

// Post the job to social.

// Update the visibility of the job so that only the targeted audience that is allowed to see the job could see the job.

// Send an email to the customer letting them know their job is active.

}

}

}Also, injecting all the dependencies in there would be a coupled mess.

Back to the story,

To make matters worse, we just kept identifying more and more things that needed to happen after we verified a job.

function postJobCreatedHooks (jobId: string) {

// Charge the customer.

// Add the job to our queue of new jobs for the week.

// Trigger a gatsby build to rebuild our Gatsbyjs site.

// Post the job to social.

// Do a bunch of other stuff.

// Send an email to the customer letting them know their job is active.

// and more...

// and more......

}In the architecture world, we call this way of coding a big ol’ Transaction Script.

Transaction Scripts

Generally speaking, there are two main ways to organize your backend code.

Using a Transaction Script or a Domain-Model.

A transaction script is a pattern documented by Martin Fowler. It's a procedural approach to handling business logic. It's also the simplest form of expressing domain logic that works really well in simple apps.

Transaction Scripts are an excellent choice for CRUD apps with little business logic.

The reason why a lot of CRUD apps that become more and more complex fail is because they fail to switch from the transaction script approach to a Domain Model.

Switching to a Domain Model

There are plenty of excellent topics in Domain-Driven Design to address, but one of best things about DDD is the concept of “Domain Events”.

Domain Events

Domain Events signify that something significant to your domain has just occurred.

Doing a workshop-based activity called Event Storming, you can quickly identify all the relevant Domain Events that exist in your problem domain.

Sometimes, when one event occurs, it might signify that other events need to occur in reaction to it. That’s not always the case. But when it is, it allows for some really elegant and expressive ways to structure business logic.

This is what happens to our architecture when we post a job using Domain Events.

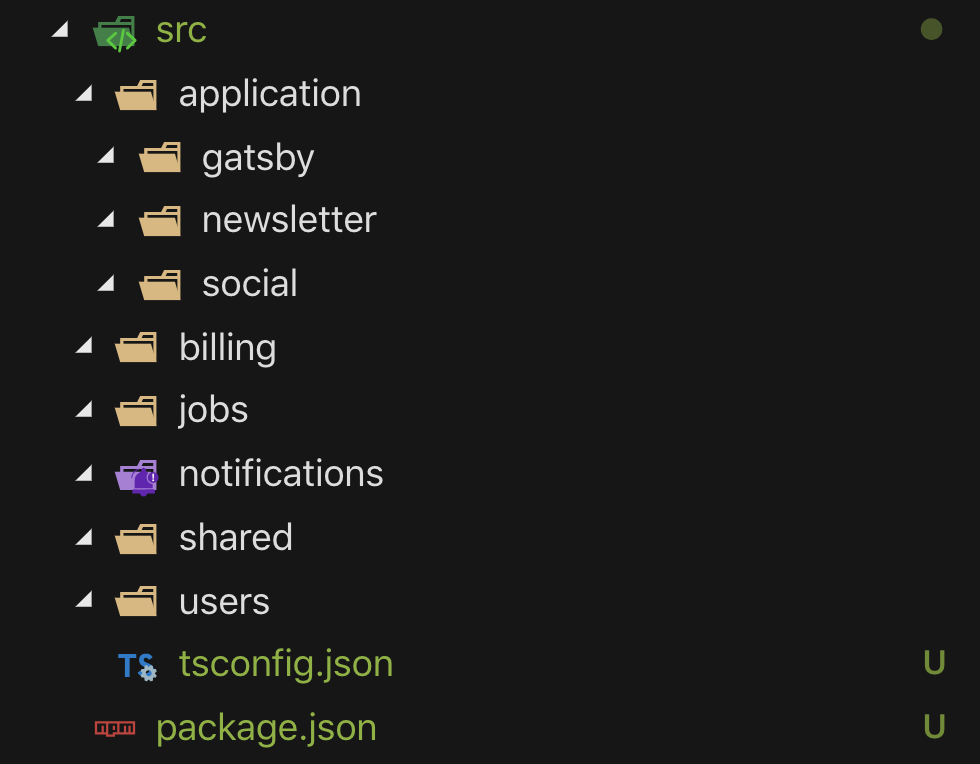

If we're using Package by Module*, the Jobs module (also referred to as a subdomain) can dispatch a JobVerified domain event.

class JobVerified extends IDomainEvent {

public job: Job;

constructor (job: Job) {

this.job = job;

}

}Then, other modules (or subdomains)* that are interested in that event can subscribe to it, and carry out their own business logic from their respective module.

OK, so I know we just used a few new terms there.

What's a subdomain? And what does Package by Module mean?

Subdomains and Packaging by Module

In Domain-Driven Design, a subdomain is way to decompose your problem domain into sub-domains. These usually reflects some organizational structure (billing, users, notifications, hr, etc).

And packaging by module refers to how we choose to arrange our code in folders. In this case, we arrange our code by subdomains, which is more readable than packaging by infrastructure where that top level of folders is organized by the type of technical artifacts it contains (/controllers, /routes, /views, etc.. blehh).

Because the entire application is deployed in a single Bounded Context, this makes for communication between subdomains using Domain Events really nice and easy, as I can hook up messaging between them over the same process.

In DDD, we call a deployment of any number of subdomains, a bounded context.

Single Bounded Context

So in my example, because my monolith is running in a single process, that's a single bounded context.

And as long as we’ve packaged our application by module/component, we can eventually split them up into microservices. That means a single bounded context per subdomain. A 1-to-1.

That’s what we could do if we needed to scale out. We could have separate teams manage separate parts of the enterprise and integrate with each other.

But, I’m not ready to take on that challenge of managing all of those separate deployments today. I’m sticking with the monolith architecture for a while longer.

If you don't understand this whole bounded-contexts and subdomains thing yet, don't worry. It requires a lot more explaination to fully grasp. It took me a little while to get. I'll write about them some more in the Domain-Driven Design Series. I'll also cover how to create Domain Events and how to subscribe to 'em.

In conclusion,

Here's what I think the main takeaways should be from this article:

Know when we need a domain model

When we realize that we're getting a lot of business logic and rules that don't quite fit within the CRUD confines, it might be a sign to move from a transaction script to domain modeling.

Frameworks aren't a silver bullet

Frameworks, like Nest.js help us become productive a lot faster, and they help by making architectural decisions for us, but we still need to learn how to do domain modeling (or something else fancy) if our CRUD app becomes sufficiently complex.

Frameworks can't always make that decision for us.

DDD is an introduction to some really interesting architectures

DDD is a gateway to some really interesting event-driven architectures like CQRS (command query response segregation) and Event Sourcing.

Stay in touch!

Join 20000+ value-creating Software Essentialists getting actionable advice on how to master what matters each week. 🖖

View more in Enterprise Node + TypeScript